When the Newsroom Becomes a War Zone

By Maya Gandhi

Attacks against the free press have surged in the United States in 2018, as newsrooms of all sizes have logged an increased number of threats and, in some cases, have suffered acts of violence. But while threats against the media are nothing new, especially in today’s hyperpartisan climate, it will take broader support from the U.S. public to combat this dangerous phenomenon.

In August 2018, CNN anchor Brian Stelter aired a recording of death threats made against him and his colleague Don Lemon, when a caller to C-SPAN declared that he intended to shoot the two journalists.

Weeks later, New York Times reporter Kenneth Vogel shared a voicemail he received in which the caller taunted him by saying “although the pen might be mightier than the sword, the pen is not mightier than the AK-47,” according to Newsweek.

Days after that, a California man was arrested and charged by the FBI after threatening to kill employees of The Boston Globe in a series of menacing phone calls, according to The New York Times. The caller, Robert Chain, owned multiple firearms, including a newly purchased rifle.

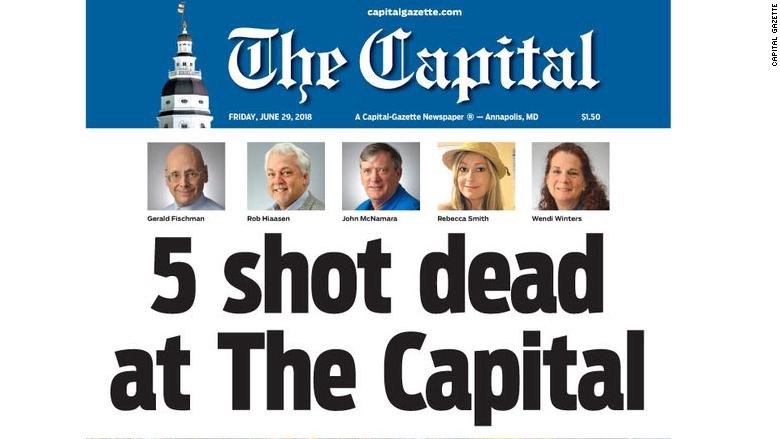

And, in June 2018, five people were killed in Annapolis, Maryland, when a gunman opened fire in the newsroom of the Capital Gazette, a local paper. The shooter was motivated by a long-standing grudge against the paper, according to The Baltimore Sun. One witness who spoke to The Sun described it as a “war zone.”

The five killed were Rob Hiaasen, an assistant editor and columnist; Wendi Winters, a community correspondent; Gerald Fischman, an editorial page editor; John McNamara, a staff writer; and Rebecca Smith, a sales associate, according to The Sun.

Violent threats, attacks, and plots against the media are often grounded in racism and misogyny, as demonstrated by an aggregation of reader correspondence published by HuffPost in the wake of the Capital Gazette shooting.

This phenomenon, already long rooted in U.S. politics, now appears to be spreading, across the nation, across parties, and across media.

And, of course, it is exacerbated by the rhetoric of President Donald Trump.

Since entering entering the political arena, Trump has consistently derided mainstream news outlets, calling critical stories about him “fake news,” attacking the “failing” New York Times, and describing The Washington Post as a “disgrace to journalism” in his frequent hostile tweets.

The president has also famously labeled journalists “enemies of the people,” in repeated attempts to delegitimize straightforward coverage of him. Evidence shows that this rhetoric is gaining traction: An August 2018 poll by Ipsos, a research firm, found that 29% of the U.S. public agrees with the notion that “the news media is the enemy of the American people,” including a startling 48% of people who identify as Republicans.

Perhaps that explains why, when Robert Chain called into The Boston Globe to air his grievances, he invoked this very notion. “You’re the enemy of the people,” he said in that phone call, according to The New York Times.

It’s not a coincidence that some of the most powerful authoritarian regimes in the world — China and Russia, to name two — have the most troublesome relationships with free, independent media. Or that as Turkey has slid away from democracy, the freedom of its journalists has quickly disappeared: The most recent statistics from the Committee to Protect Journalists show that 73 journalists were imprisoned in Turkey as of 2017 for seeking the truth and reporting it.

There is now reason to fear for the welfare and physical well-being of America’s free press. Its continued ability to hold public figures accountable, without fear of bodily or existential harm, is, of course, vital to a flourishing democracy.

Fortunately, members of the press are fighting back — or, at least, trying to — with the power of their words, vigorously defending their work amid waves of criticism. In a September 2018 article in The Atlantic, Chuck Todd, host of “Meet the Press” on NBC, called on his colleagues to take more effective action.

“If journalists are going to defend the integrity of their work, and the role it plays in sustaining democracy, we’re going to need to start fighting back,” Todd wrote. “Instead of attacking rivals, or assailing critics — going negative, in the parlance of political campaigns — reporters need to showcase and defend our reporting.”

Yet, at the same time, when journalists do attempt to advocate for themselves and the role they play in society, they are often criticized. The stereotype of the whiny, self-aggrandizing journalist has pervaded the media ecosystem, exacerbated by the cliched perceptions of so-called “media elites.” Even Stelter, when he discussed the direct threats against him, noted that he wasn’t “asking for sympathy,” as if to anticipate such critiques.

Journalists are not policy activists: The mission of U.S. journalism has never been to take aggressive stands. The case is no different here — journalists are limited in their ability to advocate for themselves. So the public must do the job for them.

It is up to enlightened citizens to recognize the serious threats that journalists face today, to underscore the intrinsic value of an unrestrained press, and to call out and combat the corrosive rhetoric that continues to portray today’s media as enemies of the state and of the people.

The U.S. free press performs a service our country desperately needs and, in this media environment, the American public must step up to advocate for it — not only for the health of our democracy, but also out of respect for the five fallen journalists of the Capital Gazette.

Maya Gandhi is a member of the Class of 2020 in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, studying international history. Originally from Tampa, Florida, she has worked for The Hoya throughout her time at Georgetown, previously serving as an executive editor.