Laws Banning ‘Fake News’: A Growing International Trend?

By Maya Gandhi

As the recent rise of misinformation has eroded trust in institutions, several countries have taken legislative steps to combat “fake news.” It sounds like a simple and noble effort, but these governmental attempts to counter false information bring with them serious threats to Free Speech, including challenges to press freedom and political dissent.

In April 2018, the Malaysian parliament passed a law to clamp down on “fake news.” Under the Anti-Fake News Act, the creation or dissemination of false or even partially incorrect information could lead to fines of up to $130,000 or a maximum of six years in jail for offenders.

The law defines “fake news” as “news, information, data and reports which is or are wholly or partly false” and criminalizes the intentional production or dissemination of “fake news.” The law applies not only to Malaysian citizens, but also to anyone else — anywhere — who spreads “wholly or partly false” information about Malaysia or its citizens.

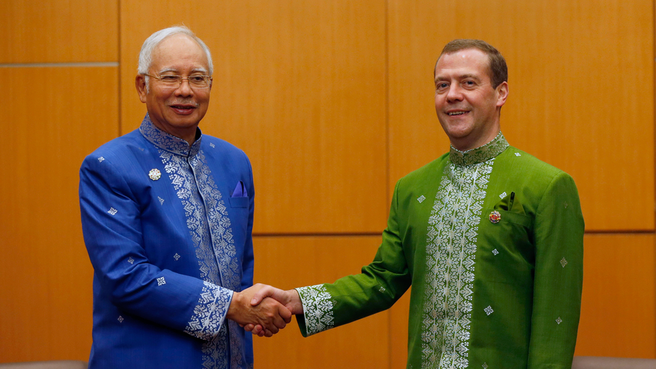

The Anti-Fake News Act came onto the scene just a month before the May 9 Malaysian general election, and in the wake of a scandal surrounding former Prime Minister Najib Razak, who has been accused of taking $700 million from a state-owned investment fund for his personal use. In a massive upset, Najib was voted out of office, losing to opposition leader and former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and ending the ruling coalition’s 60-year hold on power.

Najib was a strong proponent of the Anti-Fake News Act, leading to concerns the law would be used to silence his opponents. In the weeks before the election, Mahathir was investigated under the “fake news” law for claiming his plane had been sabotaged in an effort to prevent him from registering as a candidate for prime minister. The investigation has only bolstered critics’ fears that the new Malaysian law will be wielded by the government to silence dissent. Mahathir, who was sworn in May 10, has said he intends to amend the “fake news” law but not to revoke it.

Though Malaysia is the only country thus far to pass a law specifically aimed at “fake news,” many others are considering similar legislation. The parliament of nearby Singapore, for example, is weighing a possible law to counter “fake news,” and it held hearings in March to obtain testimony about its potential effects. French President Emmanuel Macron also pledged to introduce a law against “fake news” by the end of 2018.

Similar laws have been proposed in India and the Philippines, and the United Kingdom plans to implement a “dedicated national security communications unit” to tamp down misinformation in the public discourse. A recent German law to curb hate speech on social media also sought to address the spread of “fake news.” That law, which passed in June 2017, cracks down on web sites that do not remove hate speech, “fake news,” and other illegal materials — such as child pornography — within 24 hours.

Certainly, combating misinformation is an important international issue that laws against “fake news” might help to address. Such laws could also, for example, increase trust in institutions and place a newfound emphasis on media literacy. As Macron told journalists in January, the proposed French legislation would be a “legal means of protecting democracy against fake news.”

Nevertheless, “fake news” laws introduce a number of Free Speech qualms. Their broad and sweeping nature endows governments with immense power by allowing them to decide what is “fake,” rather than just erroneous, incomplete, or biased. For example, Macron’s proposed law would grant judges emergency power to block particular content during election cycles, introducing the possibility of widespread censorship.

“Fake news” laws also have the potential to threaten press freedom and stifle opposition, particularly critiques of corrupt governments or of those that violate democratic norms. Clearly, these fears have already become salient in the case of the Malaysian law.

The French newspaper Le Monde, in response to Macron’s proposed measure, argued in an editorial that “fake news” laws could have detrimental effects on press independence, saying that the legislation “on a subject as crucial as the freedom of the press, is by nature dangerous.”

In addition to their legal implications and their potential use by authorities to stifle dissent, the laws could foster a culture of preemptive self-censorship, leading to chilling effects on Free Speech and discourse.

Some attribute international efforts to take on “fake news” in part to U.S. President Donald Trump’s antagonistic rhetoric toward the media, including his penchant for the term — often invoked as a tactic to discredit negative coverage of him. As The New York Times’ editorial board wrote, politicians around the world have seen Trump’s attacks on the media “as a green light to crack down on the press.”

“Fake news” laws have the potential to become an international trend, as they are already spreading to countries throughout Europe and Asia with a variety of forms of government. As such legislation becomes more common, press freedom and political dissent may well be seriously undermined.

Maya Gandhi is a member of the Class of 2020 in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, studying international history. Originally from Tampa, Florida, she has worked for The Hoya throughout her time at Georgetown, previously serving as an executive editor.