Sharing Is Caring? Tracking State Adoption of ALEC’s Campus Free Speech Legislation

By Gustav Honl-Stuenkel

The coronavirus crisis has highlighted a perennial tension in the U.S. political system between the state and federal governments. Debates over Free Speech also reflect this rift, especially when centered on college campuses. Despite the national importance of Free Speech in these times, the federal government actually wields little influence over the policies pursued even by public colleges and universities, which are subject first and foremost to state regulation.

But this reality has not stopped national political organizations from attempting to bridge the gap between the national preoccupation with Free Speech and disparate state policies on the issue.

A bill spearheaded by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), making the rounds of state legislatures, illuminates the drama.

In May 2017, ALEC unveiled the Forming Open and Robust University Minds Act, or FORUM Act. According to Scott Kaufman, director of the Education and Workforce Development Task Force at ALEC, the FORUM Act is “a set of best practices” that may not be practical or necessary in every state. “Ultimately,” he says, “it is up to state legislatures to decide if a model policy is right for them.”

Thirteen states, as of May 2020, have advanced the bill in some form.

Five aspects of the legislation address different elements of the Free Speech debate. The model bill eliminates “free speech zones” — public areas set aside for political protest — on college campuses and designates all outdoor space as a public forum; it insists that all student groups, including religious, ideological, and political organizations, receive the full benefits offered by a university, even if those groups require their members to follow certain beliefs and standards; it requires public colleges and universities to file an annual report on Free Speech and expression on their campuses; it guarantees individuals the right to sue a public institution if its alleged violation of the FORUM Act harms them; and it redefines what forms of conduct and speech constitute “harassment” and, thus, what speech can be punished by universities.

These components provide a framework from which state legislators can modify the FORUM Act as they choose. Some of these provisions bear further explanation, however.

Free Speech zones are public areas set aside for political protest on college campuses and have been the subject of numerous lawsuits in recent years. In an interview with the Free Speech Project, Diana Ali, associate director of research and advocacy for the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA), said: “Free Speech zones are sometimes used … to limit the campus presence of those unaffiliated with the institution [in] order to uphold the educational purpose of the campus community.” While NASPA has not released an opinion on the litigation around Free Speech zones, Ali acknowledged their usefulness in this respect.

According to Kaufman, however, this protection of voices, even from outside the campus, is precisely the point: “Public universities are government institutions,” he explained, so the legislation aims to balance “the rights of an individual or group to express a viewpoint and another individual or group to express a counter-viewpoint” in that public space, regardless of whether they are members of that campus community.

The FORUM Act also ensures that universities cannot deny benefits to any student organization based on the group’s speech or whether it requires its members and leaders to “affirm and adhere with the organization’s sincerely held beliefs” or “comply with the organization’s standards of conduct.” This provision appears to anticipate lawsuits like the one taken against the University of Iowa, which allegedly violated a Christian student group’s Free Speech rights by de-registering it because its statement of faith excludes LGBTQ students, according to Inside Higher Ed.

That provision has drawn sharp criticism. In January 2018, for example, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of West Virginia came out against the FORUM Act when the state legislature took it up. “The bill is largely a campus free speech bill that … ACLU-WV would probably support” under ordinary circumstances, its press release says. But it goes on to complain that the legislation “would essentially wipe out school non-discrimination policies as applied to student clubs.” Public universities accept both taxpayer money and funds paid directly by their students. Because of this, ALCU-WV maintains, they should not be forced to fund all clubs: “a Jewish student at [West Virginia University] could be forced to pay a student activity fee that funds a club that prohibits Jews from membership. It would be outrageous.”

The FORUM Act’s definition of harassment, which is included in new U.S. Department of Education Title IX regulations set to take effect on Aug. 14, 2020, has attracted similar criticism. In 2013, during the Obama administration, the Department of Education told the University of Montana to adopt a definition that was entirely subjective, one with which most universities have since aligned. The FORUM Act’s definition asserts that expression must be “subjectively and objectively offensive” to be considered harassment. Changing the standard for what is considered harassment reduces the range of actions and speech for which universities can punish their students, protecting their Free Speech rights but also, opponents argue, protecting what some would consider harassment.

Free Speech debates are notorious for defying typical partisan divisions. As can be seen with the elimination of Free Speech zones, protections for student organizations, and even the simple definition of a term, all sides can justify their stance legally and rationally. In this way, conservative and progressive organizations alike have taken steps to defend the First Amendment, and universities have long served as flashpoints for these debates. Legislation like the FORUM Act will undoubtedly set the terms of debate and determine the status quo in state legislatures around the issue for years to come.

What states have included in their versions of the FORUM Act:

| State | Eliminate Free Speech zones | Protections for student organizations | Free Speech reports | Relief for those affected by violation | Definition of harassment |

| Alabama | x | x | x | x | x |

| Arkansas | x | x | x | x | x |

| California | x | x | x | x | |

| Georgia | x | x | x | x | |

| Iowa | x | x | x | ||

| Louisiana | x | x | |||

| Maryland | x | x | x | x | |

| Mississippi | x | x | x | x | x |

| Ohio | x | x | x | ||

| Oklahoma | x | x | x | x | |

| South Carolina | x | x | x | x | |

| Washington | x | x | x | ||

| West Virginia | x | x | x | x |

Political Canvassing: Door-to-Door Free Speech

By Gustav Honl-Stuenkel

“Soliciting’s not allowed in this neighborhood, so I’m gonna need you to get off my property and get out of this neighborhood before I call the police,” John said gruffly, bursting through his door before I even had the chance to knock.

“I’m not selling anything sir; this is canvassing, and it’s regarded as political speech,” I responded, though I knew right away that the best I could hope for from this interaction was the chance to move on and talk with someone at the next house on my list.

“No!” he snapped. “Any time you’re going door-to-door and talking to people, it’s soliciting and it’s not allowed here. Now get out of this neighborhood — it’s a left at the end of the street, and I’m gonna watch you walk out.”

“All right, have a nice day,” I murmured and turned around. As I walked away, I could hear John a couple yards behind me. He paused at the end of his driveway as I moved faster and wiped the cold sweat off my palms. The next house on my list was midway down the block, but I swiveled around to see John, hands on hips, still standing there, making sure I left the neighborhood. I gave him a little wave (trying my best to seem nonchalant) and turned left.

I took my first breath in what felt like hours, sipped some water, and tried to calm my pounding heart. There were about 50 more houses in the neighborhood I was supposed to canvass, so I looked up another address, took a deep breath, and walked on.

This scene occurred last summer, when I was an intern on a congressional campaign in Washington state that many pundits have identified as one of the closest races of the season, and one essential for Democrats to win to retake control of the House of Representatives. Three candidates vied for the party’s nomination, making it a contentious primary race to the finish line. Before Washington’s Aug. 7 primary, our campaign had a goal of speaking personally to 70,000 people through in-person canvassing; by the day of the primary, we had actually knocked on more than 80,000 doors. While we didn’t talk to someone at every door, our eventual margin of victory probably depended on the face-to-face contacts our canvassers made before the primary. Canvassing is essential in political campaigns. Our result shows it, and the results of countless studies reinforce it.

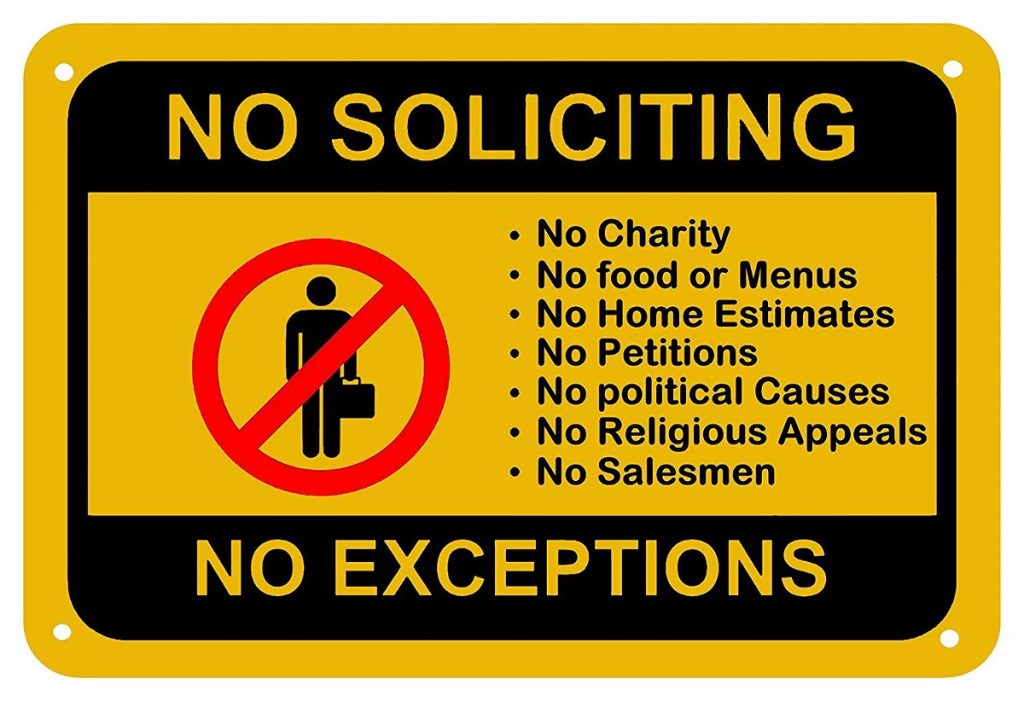

But as a canvasser, one sees the full gamut of ways people can tell you to go away. The most common, and most misunderstood, is the “No Soliciting” sign. Be it a faded, peeling sticker on the door, or a plaque with an in-depth explanation of the many different disturbances caused by knocking at this particular door, “No Soliciting” signs are a common means for a household to try to avoid unwanted conversations with strangers. For many who put up such signs, these conversations include sales, religious proselytizing, fundraising, and political campaigning.

According to a number of court cases, however — most recently Citizens Action Coalition vs. the Town of Yorktown, Indiana, decided by a federal district court in 2014 — door-to-door canvassing is considered political speech and thus is protected by the First Amendment. Yorktown, a small and predominantly rural community in southern Indiana, passed an ordinance banning door-to-door solicitation before 9 a.m. and after either 9 p.m. or sunset, whichever comes first.

The ordinance specifically targets any “person who goes door-to-door for the purposes of disseminating religious, political, social or other ideological beliefs,” which “includes any person who canvasses or distributes pamphlets or other written material intended for non-commercial purposes.” The ordinance makes it clear that it means to include political campaigning and fundraising. But as the court decision against the town explained, sunset occurs in Yorktown before 8 p.m. more than six months of the year, and it occurs earlier than 5:30 p.m. for a number of days in December — considerably narrowing the window for traditional door-to-door campaigning.

The Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana (CAC), a group of advocacy organizations that relies on donations earned through door-to-door and phone canvassing, sued the town. Judge Richard Young, of U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, ruled summarily that ordinances such as this one infringe on individuals’ First Amendment rights.

Similar court decisions have been handed down since 1938, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Lovell vs. the City of Griffin, Georgia, that requiring a permit to distribute “circulars, handbooks, advertising, or literature of any kind” violated freedom of the press, and freedom of speech and free exercise of religion as well. That case set an important precedent for broadly allowing canvassing and the distribution of flyers, declaring it a form of protected speech. Subsequent cases, including City of Watseka vs. Illinois Public Action Council and the 2014 Yorktown case, have further defined permissible time, place, and manner restrictions on soliciting. The Watseka case concluded that restrictions must be “content-neutral … leave open ample alternative channels for communication, and [be] narrowly tailored to serve [a] government objective,” such as residents’ safety. All the cases reinforce the bedrock notion that noncommercial canvassing, as a form of political speech, is protected by the First Amendment, and may not be abridged in the same way as door-to-door peddling.

So what does that mean for John’s “No Soliciting” sign in the Seattle suburbs? In short, it is irrelevant to noncommercial home visits, be they for the purpose of religion, government, or politics. For campaigns, this means we can do our jobs enthusiastically and thoroughly, contacting as many potential voters as possible and building support through face-to-face interaction, rather than constantly flooding the airwaves and mailboxes with advertisements. Some may regard it as a nuisance, and they certainly have a right not to answer the door or to slam it shut, but to me, canvassing seems like a human and worthy, even noble, way to sustain democracy.

Gustav Honl-Stuenkel is a member of the Class of 2020 studying philosophy and government in the College and is originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota. He has studied abroad at Sciences-Po in Lyon, France, where he examined French politics, especially regarding free speech norms.

When Rap Lyrics and Free Speech Collide

By Gustav Honl-Stuenkel

“Enough elementary schools in a ten-mile radius to initiate the most heinous school shooting ever imagined, and hell hath no fury like a crazy man in a kindergarten class.”

This sentence, in a note left at an elementary school, in an angry post on social media, phoned into a police station, or otherwise expressed in prose, would naturally be seen as a grave and criminal threat. For Anthony Elonis, however, these words — menacing, offensive, and violent as they may be — are simply a verse from a rap song he wrote, and according to the Supreme Court, they are protected by the First Amendment. This context, that the words come as a form of artistic expression rather than standing alone, is critical to determining where lines of Free Speech are drawn, and what artists can and cannot say.

Various genres of music have been decried publicly for their presumed impact, from heavy metal being blamed for the suicide of two teens, to drill, a style of rap, recently being blamed for an uptick in knife violence in London. Rap music, as it has ascended to become the most popular genre in the world, has especially been a target of these accusations. As has been the case throughout its development, rap is peppered with hyperbolic references to drugs, alcohol, weapons, and violence. For many, this has been a reason not to listen to the genre, to ban it from radio and television, and to call the artists who make it thugs, criminals, and threats to society; for lawyers, these traits, and the lyrics they inspire, can be especially powerful in a courtroom. The cases of Elonis v. United States, Skinner v. New Jersey, and Oduwole v. Illinois, among others, all centered on rap lyrics found by prosecutors to secure convictions specifically regarding the alleged intent to commit violence. The artistic context of each case was important for the convictions at trial and ended up being important again as each conviction was overturned by higher courts.

Anthony Elonis’ case especially demonstrates how context outlines the protections for artists. In 2010, Elonis was accused of threatening his ex-wife through rap lyrics that he posted on Facebook, though he included disclaimers in the comments section that these lyrics were artistic expression and asserted that they were protected by the First Amendment. When Elonis was taken to court, the prosecutor’s argument was that a reasonable person would feel threatened by the words, given the context in which they were delivered. “It’s a virtual certainty” that one would feel threatened by the lyrics Elonis posted, The New York Times reported the prosecuting lawyer as saying.

This approach secured a guilty conviction in lower courts, but when the case reached the Supreme Court, the justices focused on determining whether there was criminal intent behind the lyrics. An amicus brief, filed by Erik Nielsen and Chris Kubrin for the First Amendment Project, referenced the cases of both Oduwole (in which the rapper was accused of making terrorist threats) and Skinner (in which the singer was accused of murdering a drug dealer) in explaining how courts can easily misconstrue the braggadocio and exaggeration prevalent in rap music as genuine reflections of the intent of the writer.

Through this misperception, the brief concludes, Elonis’ lyrics were misinterpreted and thus used improperly as evidence of his intent. A similar situation occurred with Skinner, whose rap lyrics were entered as evidence of “motive and intent” of the murder for which he was on trial. In appellate courts, however, the use of these lyrics was deemed prejudicial, and the ruling was overturned. The First Amendment Project’s brief argued that the subjective intent of the writer should be the focus of a case such as this, and that otherwise, Elonis’ right to free artistic expression would be infringed upon, as it had been for Skinner.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Elonis, saying that the prosecution did not prove that his wrongdoing was evident to him, and that the threshold for threats should not be whether a reasonable person would view his words as a threat without being conscious of the defendant’s state of mind when he uttered them. The court contended that without proof that Elonis intended his words to be threats rather than lyrics, a conviction based on his expression could not stand. The justices ruled that while artistic expression may seem threatening, there must be proof that the artist intended the threat — otherwise, art is protected.

The First Amendment affords Anthony Elonis, as a U.S. citizen, great latitude with what he can and cannot say publicly, be it online or in person. If he chooses to make threats, however, Elonis crosses a clear boundary that the government has established, and his words themselves become a crime. These threats, however, when put to verse and laid over music, become artistic expression, raising the bar for proof and changing how the courts must weigh them as evidence. As shown by Elonis v. United States, artistic expression offers its own layer of protection, affording artists and creatives the space to communicate freely, and to broach controversial topics, seemingly as long as they don’t mean to act upon what they say.

Gustav Honl-Stuenkel studies philosophy and government in the Georgetown College Class of 2020. He writes and served as podcast editor for the Georgetown Voice and is a tutor for the Writing Center.