The Bassett Affair: Duke University’s Early Encounter With Free Speech and Racism

By Sue Wasiolek

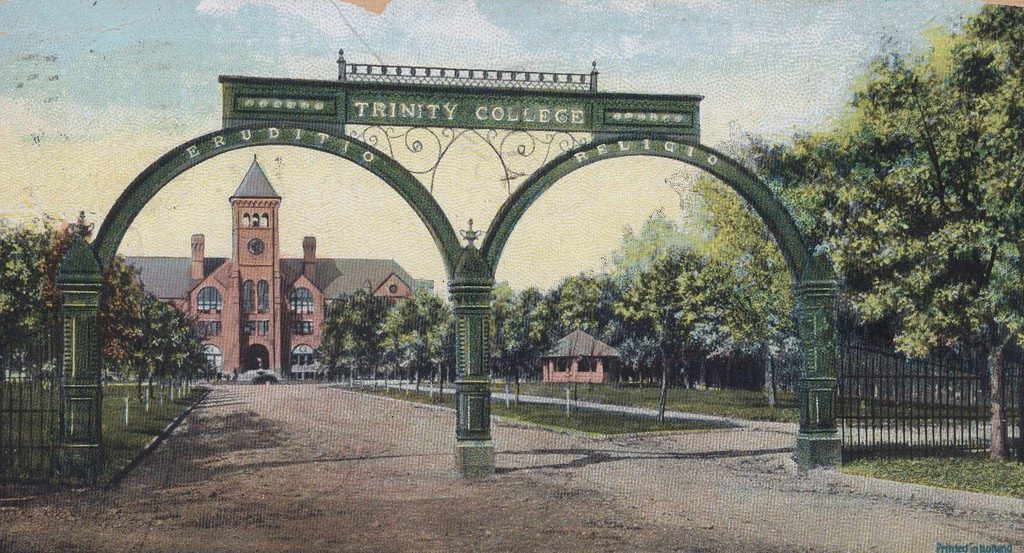

Although it was expected to be a defining moment for Trinity College, in North Carolina, and put it on the map as a top-notch liberal arts institution in the early 1900s, the “Bassett Affair” may not have had the broad impact originally anticipated. Nonetheless, this episode was important in the history of the institution that would become Duke University, and it may provide guidance to the enduring struggle over the meaning of Free Speech in higher education today.

Born in 1867 in Tarboro, North Carolina, to devoutly Methodist parents, John Spencer Bassett was the second of seven children. He enrolled as a junior in 1886 at Trinity, a church school, where he was influenced by the new president, John Crowell. Graduating from Trinity in 1888 and serving as a public school teacher, Bassett returned to his alma mater as a history professor after earning his doctorate at Johns Hopkins University in 1894. In 1902, he founded the South Atlantic Quarterly, “a journal devoted to the literary, historical, and social development of the South,” with the goal of promoting the “liberty to think,” according to the Duke University Archives.

Bassett was not afraid to address issues of race in his articles. He praised the contrasting philosophies of both Booker T. Washington, who argued in favor of gradual vocational education for African Americans as a way of advancing the community, and of W. E. B. DuBois, who advocated for a more radical approach to be led by a “talented tenth” of Black intellectual elites. In an effort to gain attention and confront the bitter debate over racism and segregation that roiled a deeply divided South, Bassett published a piece in 1903 describing Washington as “all in all the greatest man, save General Lee, born in the South in 100 years.” This praise for a Black man created an angry response from members of the Democratic Party, the public, and the media, who viewed Bassett’s support of Washington as a threat to the accepted way of life in the South.

The uproar was so severe that Bassett found it necessary to offer his resignation from Trinity’s faculty. By a vote of 18-7, the college’s board of trustees decided to decline his offer in the name of academic freedom, and Bassett remained at Trinity until 1906, when he left for a faculty position at Smith College in Massachusetts. In its decision, the board stated, “We are particularly unwilling to lend ourselves to any tendency to destroy or limit academic liberty. … We cannot lend countenance to the degrading notion that professors in American colleges have not an equal liberty of thought and speech with all other Americans.” And so began — at least at one prominent liberal arts college in the South — the concept of academic freedom for college faculty and freedom of speech for others on higher education campuses.

As we review this debate that took place more than 100 years ago through a contemporary lens, we can’t help but acknowledge that, ironically, Bassett was criticized not for admiring Robert E. Lee — a white leader of the Confederacy, statues of whom have recently become the object of protest, vandalism, and violence around the country — but for his praise of Booker T. Washington, a leading Black thinker and activist.

Drawing the line as to what constitutes free speech has not become much clearer as we attempt to enable our institutions to be places where different perspectives, opinions, and ideas can be discussed, while ensuring the safety and support of all members of the campus community. I can think of no better illustration of the current state of freedom of expression on college and university campuses than to consider the polar opposite opinions of two academic leaders. Jay Ellison, dean of students at the University of Chicago, wrote in 2016:

“Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.”

Soon thereafter, the president of nearby Northwestern University, Morton Owen Schapiro, expressed an opposite view in his convocation address to the incoming Class of 2020:

“The people who decry safe spaces do it from their segregated housing places, from their jobs without diversity — they do it from their country clubs. It just drives me nuts.”

How do we reconcile these contrasting instincts, and how might the Bassett Affair provide guidance to us? Is college and university life today so different from 1906 that John Spencer Bassett’s situation has become completely irrelevant?

Over the years, many colleges and universities across the country have had to deal with student-sponsored parties and gatherings with inappropriate, offensive, and unfortunate themes. For example, the “ugly woman contest” at George Mason University in 1991 resulted in disciplinary action against the fraternity sponsor because of a racially and sexually offensive skit that the university felt created a “hostile and distracting learning environment” for many of its students. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit overturned the discipline of the fraternity, ruling in 1993 that its members’ “sophomoric” conduct was protected by the First Amendment.

Similarly, when Duke University experienced the “Viva Mexico” party in 2003 or the “Asia Prime” party in 2013, students and faculty demanded that the sponsoring fraternities be punished due to their racial insensitivity. However, Duke chose not to punish the party organizers, but instead to respond to the use of racial and cultural stereotypes through dialogue and education. This was not because it was bound by the decision in the 1991 case, but instead because it thought it was important to protect speech, even if offensive. When these decisions were made at Duke, many thought the Bassett Affair was alive and well and its precedent influenced these outcomes.

As important as the Bassett Affair was and continues to be, it was likely intended to be limited to academic freedom, namely the freedom of the faculty to inquire and teach. Considering the lack of racial, ethnic, and gender diversity of the college community in the early 1900s, as well as the locus of education being in the classroom, the Bassett decision was never meant to justify and protect all speech that takes place on a college campus, and yet many have certainly attempted to use it for that purpose.

With that in mind, are there not times when a faculty member’s teachings in the classroom and his or her use of “academic freedom” has created discomfort for students? Why is this discomfort justified and the discomfort created by Free Speech outside the classroom is not? Given that much of a student’s education in college occurs outside the classroom, wouldn’t it make sense to extend the definition of academic freedom to non-faculty?

While John Spencer Bassett’s precedent may not justify all speech on a college campus, it remains highly relevant today, as it provides an important historical backdrop for the ongoing need for faculty to be permitted to pursue and communicate knowledge without fear of being censored or disciplined. In addition, it calls the question as to whether today’s college learning environment is truly confined to those spaces occupied by faculty.

Sue Wasiolek serves as an associate vice president for student affairs and dean of students at Duke University and teaches education law at Duke and North Carolina State University. She lives in a freshman residence hall with 188 first-year students.